Israel at 70: Why Gaza’s refugees and their descendants will never forget their violent expulsion

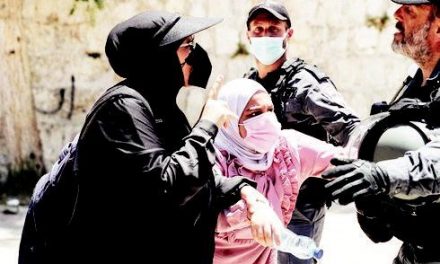

As the anniversary approached of the start of the exodus from what became Israel, an event Palestinians call the Nabka (catastrophe). Sarah Helm visits Gaza to hear the views of residents old and young about their past and future Female demonstrators run for cover from tear gas fired by Israeli forces at a protest on Friday during the Great Return March.

Looking across his oranges grove, on top of one of Gaza’s highest hills, Abu Othman lays claim to the best view of Gaza, both its past and its present.

Smiling, he points his stick east, across the barrier wall towards Israel, and traces where as a boy, before

the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, he rode his horse to visit the Arab villages of Burayr and Huj, then on the hills nearby then traces the line along which a caravan of camels used to travel, transporting supplies from Cairo, passing near then Gaza district villages and on to Jaffa.

Here was the old railway line connecting Cairo to Aleppo, the same line that brought Winston Churchill,

then colonial secretary, to Gaza in 1921, when Churchill told the Palestinians, living by then under British rule, that they must accept a Jewish homeland in Palestine, as set out by the Balfour Declaration of 1917. In his declaration, Sir Arthur Balfour, the foreign secretary, had also promised to protect rights of Palestinians who lived here.

But during the 1948 war, Britain did nothing to protect inhabitants of 200 Arab villages whose people were expelled by Israeli forces or fled interror towards Gaza City, seeking safety behind Egyptian lines, nor to protect the other 500,000 refugees who fled elsewhere. Now mukhtar (elder) of a Gaza village called Bayt Hanoun, Abu Othman saw the 1948 refugees arrive in Gaza and recalls the stories of expulsion, massacres and barrel bombings that sped their flight.

No longer smiling, he now traces lines that mark out Gaza’s present. Extending a gnarled finger west towards the Mediterranean Sea, he swings northeast and south following the barrier that encloses the coastal strip, with the Erez checkpoint, its caged walkways, gates and gantries sprawled just below us, locking in Gaza’s 2 million inhabitants – among them 1.3 million refugees – both the old who arrived in 1948 and their descendants.

“Time will cure and all will be forgotten,” said David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, which appeared to mean he expected the old refugees would die and their children would forget. But Abu Othman’s memories have never faded. “How can I forget when I look each day directly into the past?” he asks. His friend, Abu Ahmad, walks past, pausing to tell us his mother was killed in 1948 at a massacre in Dimra, the Arab village that once stood on the land on which the Erez checkpoint was built. “She was thrown in the village well with 10 others. I have never forgotten it.” he says.

Gathering along the buffer zone below us, the younger generation of Gazans were also defying Ben- Gurion’s belief that they would forget. Clouds of tear gas float up towards us. We could see tents being erected and crowds gathering, preparing for the Great Return March, which culminates on Tuesday, the 70th anniversary of the Nakba or “catastrophe”, as Palestinians call the event that lead to their expulsion in 1948.

Everyone in the Great Return March knows full well they will not be returning to their ’48 lands, as they call them – at least not any day soon. They know full well that they risk being killed by Israeli snipers by even approaching the barrier – 40 have been shot dead in the past four weeks. But for most protesters it will be an achievement just to show the world they have not forgotten what happened in 1948, even if the world has forgotten them.

The “right of return” enshrined in 1948 in United Nations Resolution 194 is felt perhaps most strongly by Palestinian refugees of Gaza precisely because so many once lived just a few miles from Gaza’s walls. Almost all the refugees who reached Gaza were village farmers, deprived of their livelihoods too as they lived off the land. Running in terror, past other burning villages, they left grapes on the vine and wheat just harvested, taking nothing with them, such was the panic. Many soon tried to return if only to get food to eat and to finish the harvest, but almost all were forced back by Israeli troops. From the end of the war the attempt to return never stopped, but Israel called returnees terrorists, imprisoning them or

shooting them on sight.

By the 1950s some Israeli leaders, most notably Moshe Dayan, its chief of staff, had faced the fact that the refugees of Gaza would not readily forget their expulsion.

In 1956, at a kibbutz called Nahal Oz, one mile from the Gaza border, a young Israeli was brutally killed

by a Palestinian refugee who had crossed back over. Dayan spoke at the dead man’s funeral, giving an

address which some have called a defining speech of Zionism.

“Why should we complain of their [the Arabs] hatred for us?,” asked Dayan, addressing the Israeli mourners. “For eight years have they sat in the refugee camps of Gaza and seen with their own eyes how we have made a homeland of the soil and the villages where they and their forebears once dwelt.”

But Dayan’s answer to this question was not to allow the Gaza refugees back, but to prepare for perpetual conflict against “hundreds and thousands of eyes and arms huddled together there … waiting to tear us to pieces”

Had he been alive today, Dayan would have seen his dystopian prediction of perpetual conflict coming true right here on the Gaza side opposite Nahal Oz, where more blood has split in the past four weeks among the “thousands of refugees huddled together” than anywhere else.

I went down to the Nahal Oz section of the buffer zone in the days before the Great Return March began and saw teenagers already hobbling from gunshot wounds and a boy who had lost half a leg, being pushed in a wheelchair. I asked them why they threw themselves in front of Israeli snipers. They shrugged and said: “It’s our duty. They are on our lands.”

Over the 70 years of conflict, there have been times of hope. The Gazans are a resilient people – “the greatest patcher-uppers in the world”, some say – and in 1993 they tried a patched-up peace plan, the Oslo accords. A Palestinian state was envisaged, constructed out of lands seized by Israel in the 1967 – the West Bank, captured from Jordan, and Gaza, captured from Egypt, were to be joined by a safe passage, and East Jerusalem was to be the Palestinian capital.

Oslo failed to address the right of return of 1948 refugees, but its two-state compromise would end the conflict, negotiators promised. I was in Gaza on the day the accords were signed, and saw euphoria well up as doves appeared on every wall. But when even the limited promises of Oslo were not fulfilled, Palestinians felt betrayed and showed it by supporting the militants of Hamas, who sent suicide bombers

into Israel. Soon Israel had put up its wall. It bombarded Gaza in a series of huge military offensives, leaving about 2,500 Palestinians dead.

When I returned in the aftermath of the most recent offensive in 2014, I was prepared for a very different place, but even the height of the wall was a shock: it had hidden the whole of Gaza from Israel’s view. In fact, the entire Gaza story now seemed hidden; Israel simply called Gaza a “terror entity”, a definition that US and the Europeans seemed often ready to accept as Gaza was now placed under permanent siege.

On the Gaza side, however, the people were remembering as never before. Such was the destruction of the 2014 war, with people made homeless and forced to live in tents again, people called it the “second Nakba”.

Memories of 1948 were literally being churned up in the rubble, in part because the two-state solution was so obviously dead and the people were looking back again to the root cause of their despair. The young were also looking back to 1948, as I heard when visiting a Rafah girls school early in 2015: “Why did Balfour give away our land?,” asked one teenager. “Why should I be a refugee when my land is 1 kilometre away?” asked another.

Moreover, the younger generation, having grown up under the siege, were exasperated by Hamas’s failure to solve their problems, scorning their leaders as “old men” whose days were numbered. “We simply want to get out of Gaza and breathe,” they said again and again. With the internet now available, they could see their old lands and search for their old villages on Google Maps. Instead of a two-state

solution, many of the young of Gaza now propose their own compromise peace formula, a “one-state solution” with Jews and Arabs living side by side.

From the top of his hill, Abu Othman thinks he has a good view not only of past and present but of the future too, and points now towards the Negev desert in southern Israel and to the Egyptian Sinai, where in both places space is being cleared, and the Bedouin are moved to “townships”.

Many in Gaza believe that these land clearances are part of Israel’s plan to carve Gaza off permanently from the West Bank, attach to it a small amount of the Negev in the east and push its southern boundary into the Sinai, with Egypt’s agreement, thus creating a bigger Gaza prison, which Israel will call a state.

“It won’t work,” says Abu Othman. “Eventually the Palestinians will return. Not soon. But eventually. God willing.”