BREAKING THE SILENCE: Malawi Confronts a Rising Suicide Crisis

By Mustafa Makumba

On a grey morning in Lilongwe’s Area 25, word spread quickly: another young man had taken his own life. The story was painfully familiar. In just the first three months of 2025, Malawi Police recorded 153 suicide cases—a sharp rise compared to recent years. Behind each number is a grieving family and a nation slowly waking up to a crisis long ignored.

Globally, suicide claims more than 700,000 lives every year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Africa carries the world’s highest regional rate, with 11.2 deaths per 100,000 people. Yet in Malawi, suicide has rarely been discussed openly. For decades, attempted suicide was criminalized under colonial-era law, deepening stigma and deterring people from seeking help.

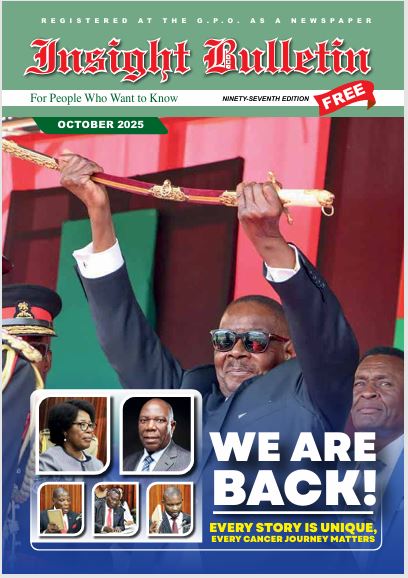

That changed in July 2025, when President Lazarus Chakwera signed the new Mental Health Act, decriminalizing suicide attempts and reframing them as a health issue rather than a crime.

“This is a turning point,” says Dr. Chiwoza Bandawe, a clinical psychologist. “People who attempt suicide are not criminals; they are people in pain. Removing the fear of punishment allows us to focus on compassion and treatment.”

The challenges, however, remain immense. Malawi has fewer than 20 psychiatrists serving a population of nearly 20 million. Facilities such as Zomba Mental Hospital are overstretched.

“We see dozens of young patients each day—many battling depression, trauma, or substance abuse,” says Immaculate Chamangwana, the hospital’s director. “But we are short on staff, medication, and space. Families want help, but the system is overwhelmed.”

Youth are among the most affected. University campuses have reported suicides linked to exam stress, financial hardship, and lack of psychosocial support. Earlier this month, the Malawi University of Business and Applied Sciences ran a Mental Health Week campaign under the theme “Suicide is not a solution.” Lecturers and student leaders urged peers to seek help and support one another.

According to Dr. Olive Liwimbi, a psychiatrist and lecturer at Kamuzu University of Health Sciences, prevention must begin at the community level.

“We cannot rely only on hospitals. Teachers, faith leaders, and community health workers all need training to recognize the warning signs of suicide. Early intervention saves lives.”

Yet stigma remains one of the greatest barriers. In rural areas, suicide is still whispered about as shameful or attributed to witchcraft. Survivors often face discrimination, worsening their isolation.

Dr. Kazione Kulisewa, Head of Psychiatry at KUHeS, emphasizes the need for cultural change:

“We must normalize conversations around mental health. Talking openly does not encourage suicide—it prevents it.”

Across the country, grassroots initiatives are stepping in. Youth groups in Blantyre’s Ndirande township run radio talk shows on coping with stress. Churches and mosques are weaving mental health awareness into sermons. NGOs are piloting peer counseling programs in schools.

World Suicide Prevention Day 2025 carried the global theme “Changing the Narrative on Suicide.” For Malawi, that narrative is only beginning to shift—from silence and stigma to recognition and response.

Campaigners say the new law, paired with growing awareness, could mark the start of a national movement to save lives. For the young man in Area 25, change came too late. But for thousands of others, it may offer hope.