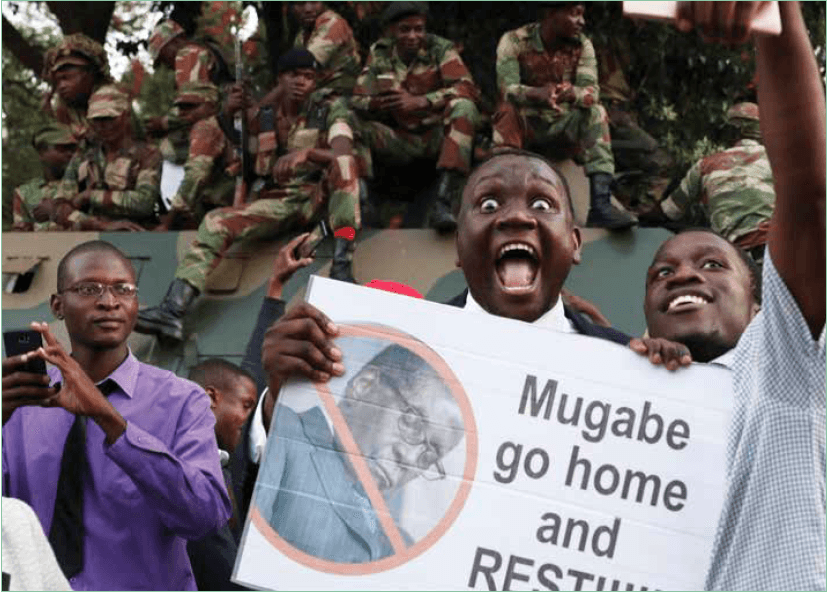

Mugabe is Gone: What Next For Zimbabwe?

For some, he will always remain a hero who brought independence and an end to white-minority rule. Even those who forced him out blamed his wife and “criminals” around him.

But to his growing number of critics, this highly educated, politician became the caricature of an African dictator, who destroyed an entire country in order to keep his job. In the end, it was the security forces that had been instrumental in intimidating the opposition and keeping him in power, which made him go.

They were incensed when he sacked his long-time ally, Vice-President Emerson Mnangagwa, paving the way for his wife Grace to succeed him, fearing it meant the end for them as the powers behind the throne.

Robert Mugabe had previously survived several crises and predictions of his demise but with his powers failing at the age of 93, his former comrades-in-arms turned on him, favoring Mnangagwa.

But who is Mugabe?

Mugabe graduated from Katuma’s St. Francis Xavier College in 1945. For the next 15 years he taught in Rhodesia and Ghana and pursued further education at Fort Hare University in South Africa.

This is where he rubbed shoulders with future African leaders such as Kenneth Kaunda and Julius Nyerere.

In 1960 Mugabe joined the pro-independence National Democratic Party, becoming its publicity secretary. In 1961 the NDP was banned and reformed as the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU). Two years later Mugabe left ZAPU for the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU, later ZANU-PF), where he built his political home.

In 1964 ZANU was banned by Rhodesia’s colonial government and Mugabe was imprisoned. A year later, Premier Ian Smith issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence to create the white ruled state of Rhodesia, short-circuiting Britain’s plans for majority rule and triggering international condemnation.

Trained as a teacher, he spent 11 years as a political prisoner under Ian Smith’s administration. He rose to lead the Zimbabwe African National Union movement and was one of the key negotiators in the 1979 Lancaster House Agreement, which led to the creation of a fully democratic Zimbabwe.

In prison Mugabe taught English to his fellow prisoners and earned multiple graduate degrees by correspondence from the University of London. Freed in 1974, Mugabe went into exile in Zambia and Mozambique, and in 1977 he gained full control of ZANU’s political and militaryfronts. He adopted Marxist and Maoist views and received arms and training from Asia and Eastern Europe, but he still maintained good relations with Western donors.

“We are non-racialist in our approach. That is, we regard an individual as an individual. And that everybody must be accorded his full political rights – whether he is white or black, educated or uneducated, rich or poor. And this is why we are, at the moment, struggling to earn for our people ‘one man, one vote’,” said Robert Mugabe as ZAPU Publicity Secretary.

The leader of Zimbabwe since its independence in 1980, Mugabe 93 was one of the longest-serving African leaders

He embraced reconciliation with the country’s white minority but sidelined his rivals through politics and force.

Beginning in 2000, he encouraged the takeovers of white owned commercial farms, leading to economic collapse and runaway inflation. After a disputed election in 2009 he reluctantly agreed to share some power with the rival Movement for Democratic Change.

In 1978 accord between Smith’s government and moderate black leaders paved the way for the election of Bishop Abel Muzorewa as prime minister of the state known as Zimbabwe Rhodesia, but it lacked international recognition because ZANU and ZAPU had not participated. In 1979 the British-brokered Lancaster House Agreement brought the major parties together to agree to majority rule while protecting the rights and property of the white minority. After winning new elections on March 4, 1980, Mugabe worked to convince the new. country’s 200,000 whites, including 4,500 commercial farmers to stay.

In 1982 Mugabe sent his North Koreantrained Fifth Brigade to the ZAPU stronghold of Matabeleland to smash dissent. Over five years, 20,000 Ndebele civilians were killed as part of a campaign of alleged political genocide. In 1987 Mugabe switched tactics, inviting ZAPU to be merged with the ruling ZANU-PF and creating a de facto one-party authoritarian state with himself as the ruling president. During the 1990s Mugabe was reelected twice, became a widower and remarried. In 1998 he sent Zimbabwean troops to intervene in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s civil war—a move many viewed as a grab for the country’s diamonds and valuable minerals.

In 2000 Mugabe organized a referendum on a new Zimbabwean constitution that would expand the powers of the presidency and allow the government to seize white-owned land. Groups opposed to the constitution formed the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), which successfully campaigned for a “no” vote in the referendum.

That same year, groups of individuals themselves “war veterans”— though many were not old enough to have been part of Zimbabwe’s independence struggle—began invading white-owned farms. Violence caused many of Zimbabwe’s whites to flee the country. Zimbabwe’s commercial farming collapsed, triggering years of hyperinflation and food shortages that created a nation of impoverished billionaires.

After a 2008 election marred by ZANUPF- sponsored violence, Mugabe was pressured by his regional allies to form an inclusive government with MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai as vice president. Even while implementing the accord, Mugabe kept up the pressure, subjecting MDC parliamentarians to arrest, imprisonment and torture.

Mugabe had no obvious anointed successor, until November 2017 when he was forced by Zimbabwe zDefense Force to resign as a leader hence people should be asking what is next for Zimbabwe? What an end, the big question remains what legacy has he left?