Refugees in Europe

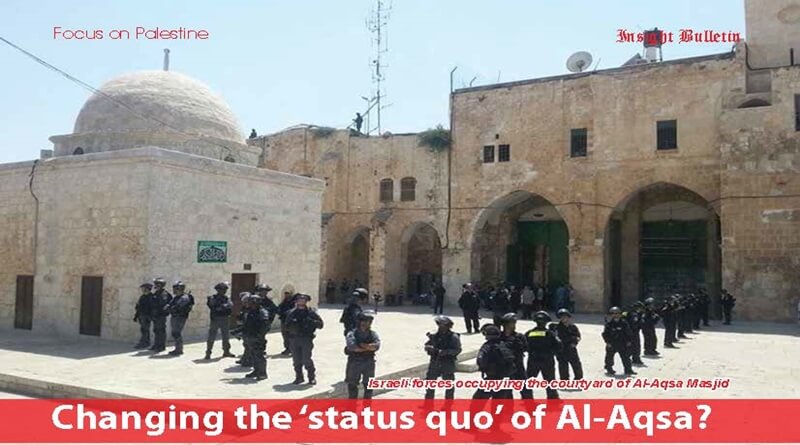

The refugee crisis currently affecting Europe has elicited comparisons to the refugee crisis resulting from the Second World War. This comparison, while worthwhile insofar as it has helped mobilise sections of the European community to assist the refugees, misses a key point: the Middle East and African regions are confronting the refugee’s crisis to a far greater extent than Europe. Europe is seeing merely fallout of the crisis that is catastrophically affecting Lebanon, Turkey and certain other Middle East nations. Refugees making their way to Europe represent barely 0.068 per cent of the total European population, while over 25 percent of the residents of Lebanon are refugees.

Refugees seeking rehabilitation in Europe are from many countries, with the largest group being from Syria. As Eurostat illustrates, the number of people seeking asylum in Europe from Syria numbered 130 000 in 2014, far more than the next largest group – from Afghanistan – numbering 40 000. The ‘refugee crisis’ is, then, primarily the result of four years of protracted war in Syria.

Unfortunately, the focus only on refugees distracts from the larger need to urgently resolve the Syrian crisis, and there is no concrete effort in this regard. Thus, even though some sectionsof European society have redeemed themselves with great humanitarian gestures and the acceptance of refugees.

Germany’s Angela Merkel and Catholic leader Pope Francis stand out amongst these, the ongoing refugee crisis is a deeper indictment of the global political elite, whether in the UN Security Council or in capital such as Damascus, Tehran, Istanbul, from where the war and violence in Syria has been fuelled without an end since 2011.

This indictment is at two levels. First, it relates to their inability to limit the spread of violence within the Middle East and Africa. And if the chaos of Syria, Iraq, Libya, Eritrea, Central African Republic, Nigeria, South Sudan and Somalia was not enough, the misery of the Yemeni people from March also lies at their doors.

Second, it points to the shambolic handling of the refugee crisis resulting from the wars the region has experienced in the past few years.

A bigger picture of the refugee crisis is necessary, as illustrated by the following facts. For 2015, the UNHCR has appealed for more than $4.5 billion just to address the needs of Syrian refugees in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt and the rest of North Africa. This does not include the six million Syrians internally displaced in their home country, and who the UN cannot access.

However, only thirty-seven per cent of these funds have been made available to the UN agency. Further, even with the global outpouring of grief for the refugees who died in the Mediterranean, especially after the widespread publication of pictures showing drowned babies like Aylan and Galip Shenu, UK prime minister David Cameron could promise to accept only

20 000 Syrian refugees over the next five years, in a radical departure from the greater goodwill exhibited by Germany.

Such data show the effective apathy of the global political elite to the suffering of these dispossessed refugees. This is compounded by another factor: the tendency of the global media and audience to take notice of an issue only when it affects white Europe or North America. While the refugees struggling to make their way into Europe are part of the media splurge witnessed from USA to Australia, and including South Africa, there is still insufficient attention being paid to refugees who are struggling to find inhabitable spaces within the Middle East and Africa.

Especially noteworthy in this regard is the movement of Yemeni refugees to the Horn of Africa. The bombing of Yemen has already created 1.5 million refugees in less than six months, but is getting barely a mention in the global fixation on the European refugee crisis’. The International Organization for Migration estimates that almost 60 000 refugees have arrived in Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan and Ethiopia from Yemen since March. It is a fair question to ask why these refugees do not get as much attention as the ones who have drowned in the Mediterranean or have been held back in Hungary.

This oversight highlights the Eurocentrism that still plagues the humanitarian concern that is driving the discussion over the ‘European refugee crisis’. Indeed, this very label should be changed, and, since it is a result of the Syrian civil war, it should be called the ‘Syrian crisis’ instead. Further, the discussion should be broadened to include refugee crises affecting other parts of the world; if the world’s concern is the well-being of refugees, then it must be understood that there are other places that also need drastic humanitarian assistance.

Above all, this refugee crisis should not become a reason to detract from the political failings of the global political elite, which can and should do more to stop wars, rather than simply bandaging some wounds created as a result of their actions.