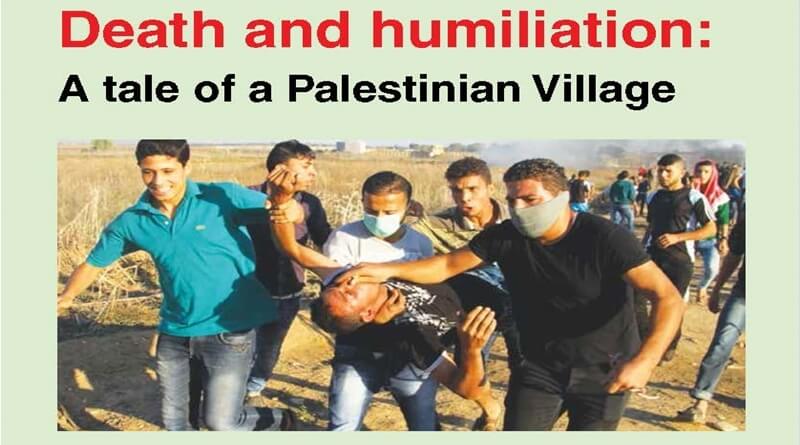

Death and humiliation: A tale of a Palestinian Village

Sa’ir, a West Bank village, is the outcome of living in the intense microcosm of the Israeli occupation.

Sa’ir, Occupied West Bank – The gathered men scramble to find their phones as news reached Sa’ir village that yet another young man from the

small rural community has just been killed. With no name known yet, frantic phone calls are made all along the main street.

Villagers pace the road, walking under freshly printed plastic banners showing the faces of the village’s youth – young men recently shot down by the now ever-present Israeli army that encircles the village and the surrounding area.

“This reminds me of before,” Mohammed Kawazba says worriedly as the scene evolves around him. “Maybe this time it could be my brother or one of my other cousins killed. This is becoming so normal now; it’s happening all the time.”

A name eventually comes through. It’s a cousin of Kawazba. There is sadness and anger in the air, but not surprise. It’s Kawazba’s fourth cousin killed by the Israeli army in a week, all involved in alleged stabbing attacks on Israeli soldiers at the nearby Beit Einun junction.

Sa’ir’s graveyard continues to fill now, as new bodies are laid down next to grey gravestones imprinted with the names of villagers killed during previous uprisings. The village of 20,000, nestled in a valley in the Hebron Hills, has seen 12 of its sons killed in the recent escalation of violence in the occupied Palestinian territories and Israel

The village makes up just one percent of the Palestinian population of the West Bank, yet seven percent of all Palestinians killed (including Palestinian citizens of Israel and residents of Gaza) since October, have come from this rural, underdeveloped community.

Sa’ir has a recent history of resistance against Israeli occupation. The village – pinpointed by Israel as a political hotspot – was hit hard by policies of closure during the second Intifada.

Situated between several Israeli settlements, and beside Road 60, one of the main arteries for settlers travelling in the occupied West Bank, Sa’ir has once again become a focal point of the Israeli army’s attention.

It is this proximity to settlers and Sa’ir’s previous political history, villagers say, that has resulted in the Israeli army clamping down hard on the village since the very first days of the escalation.

At the entrance to Sa’ir, Israeli soldiers stand fully armed, guns cocked and ready. “These are bad people,” one barks out as the only explanation as to why the main road into the village is closed.

The clampdown has resulted in village youth feeling present more than ever at the sharp end of what they describe as a brutal and dehumanising occupation.

Nine of the 12 young men killed have been involved in alleged stabbing attacks on soldiers, while the three others were shot while protesting against the army.

“I don’t know what happened,” Abu Ahmad Salim mumbles, his eyes filling with tears as he speaks of the death of his son Ahmad, who the Israeli army accused of an attempted stabbing attack

I had no idea of anything. None of the older people know what the youth are thinking.”

Now, Salim’s two other sons have had their permits to work in Israel destroyed by soldiers, and the family now fears that the army will demolish their home – a regular collective punishment tactic used against the families of alleged attackers

Practicing collective punishment and shutting off the village and refusing to let people in or out has become routine for Israeli soldiers. Settlers, protected by the increased army presence, are preventing Sa’ir’s residents from using the surrounding agricultural land – which has always served as a lifeline for the impoverished rural community.

“Sa’ir is a good example of what’s happening in the West Bank right now,” Mahmoud Kawazba, another relative of one of the recently deceased says, “but even worse”.

According to villagers, Israeli army night raids have increased dramatically, practically doubling in frequency over the past three months, with over 100 children under the age of 15 being arrested.

Older men talk of having been forced to strip their clothes and stand in the street in the freezing cold at night for no reason, while women say they’ve had their headscarves ripped from their heads by soldiers when the army makes, its now regular, and dreaded, incursions into Sa’ir.

“They close the road into the village for no reason as a punishment. The settlers provoke the youth here, and now the young people here, all they feel is hopelessness,” Mahmoud Kawazba says.

“It’s become a cycle: The soldiers humiliate and punish us, the youth protest – some might even want to attack the soldiers. If that happens, they are killed before they even get close, and it all begins again.”

Mahmoud Kawazba says that although he has some doubts over all the alleged stabbing cases, he doesn’t deny that the village youth have indeed attempted to attack soldiers – it’s a direct outcome of living in the intense microcosm of occupation that is Sa’ir.

“A lot of the village relies on farming the land around it, but more than ever, we can’t because the settlers and army will not allow us,” Kawazba continues.

“Many young people have worked in settlements and Israel, and then Israel stopped their permits. They hardly had anything before, and now they have nothing. Everyone is suffering. The atmosphere here is of depression and anger.”

With unemployment at 40 percent in the village – far higher than the average rate of 25 percent in the Hebron governorate, which already has the highest unemployment rate of any area in the occupied West Bank – and work permits rescinded, the economic situation has worsened substantially since the unrest began.

“You know, it’s like they [Sa’ir villagers involved in the alleged stabbing attacks] are off to die,” Mahmoud Kawazba says. “They have no hope, only hopelessness. The young generation in the village has nothing.”

With just nine extended families making up the community, each death hits hard, appearing to only further encourage other young men to demonstrate against the army.

Photos of the dead from the past few months are prevalent on smartphones up and down the village streets. For many residents, this constant reminder of their situation through pictures of friends and relatives, shot in the upper parts of the body in a direct attempt to kill, causes the anger to bubble back to the surface.

“Money makes money, and martyrs make martyrs,” one local quips as talk continues about the high death rate in the village.

With another young man killed and the siege on Sa’ir continuing, residents say they don’t see an end anytime soon to the current cycle of violence and death in the small rural community.