Changing the ‘status quo’ of Al-Aqsa?

The recent uprising in East Jerusalem and the Palestinian West Bank points to a clear

disillusionment among Palestinian youth, largely caused by Israel’s occupation, its Judaisation of Jerusalem, and the complicity of certain Palestinian political parties.

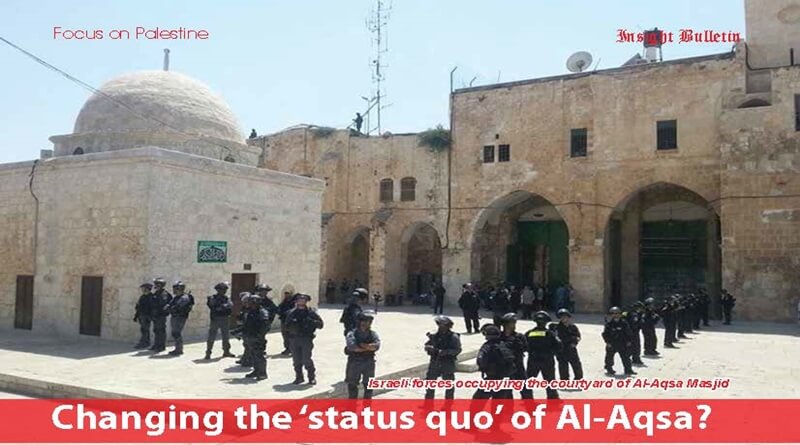

The intensification of the conflict since the beginning of October, which has caused the deaths of over sixty Palestinians and ten Israelis, was ignited by increased Israeli government sanctioning of visits of nationalist, religious Jews to the Aqsa Masjid, many of whom seek the compound’s destruction. Israel has also severely restricted Muslims access to Al-Aqsa, and increased its monitoring of Muslim groups operating at the compound. In late August and September, Israeli police prevented Palestinian women and men under fifty from visiting the Masjid before noon, and in September the Murabitun and Murabitat, informal groups of men and women who offer religious classes and attempt to ensure the ban on Jewish prayer is observed, were declared illegal.

These measures have contravened the ‘status quo’, a situation that has been in place since the eighteenth century, and in terms of which the Aqsa compound will be controlled by Muslims; people of other faiths will be allowed access to the compound but will not be allowed to pray there. This status quo has been repeatedly ratified and upheld over the past two and half centuries – even after Jerusalem was occupied by Israel in 1967, and annexed to Israel in 1980. The 1994 peace treaty between Israel and Jordan commits Israel to ‘respect the special role of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in Muslim Holy shrines in Jerusalem’. Currently, by mutual agreement between Jordan and Israel, the Aqsa Masjid compound is administered by the Jordanian Waqf. This body also, supposedly in consultation with Israel, monitors Jewish access to the site. Israeli Jewish groups entering the compound are supposed to be accompanied by police, and Waqf guides are to ensure no Jews pray on the site.

The status quo has been violated by Israel numerous times in recent years. For example, Israel often restricts Muslim access to the Aqsa Masjid compound, ranging from completely closing the Old City for Muslims to imposing age limits on those wanting to attend Friday prayers. There are also certain permanent restrictions that are less well-known. A recent privately commissioned report claims that the Israeli government has instructed that when there are Jews present in the compound, Muslim men and women under the age of 50 should not be allowed to enter. Since Israeli groups tour the compound throughout the week, this means that Muslims under 50 are not allowed access to the site every morning from Sunday to Thursday.

Further inflaming the situation, cabinet ministers, including agriculture minister Uri Ariel, who previously advocated the building of the Third Temple on the cite, visited the compound in recent weeks. This raised the ire of many Palestinians who fear the Masjid is threatened with partition, as happened to Hebron’s Ibrahimi Masjid after Zionist fundamentalist Baruch Goldstein massacred twenty-nine worshippers in February 1994 while they were praying. The latest Israeli violations resulted in protests, then running battles inside the compound between Palestinian defenders and Israelis, and culminating in a series of into lone wolf knife attacks on Israeli soldiers and settlers.

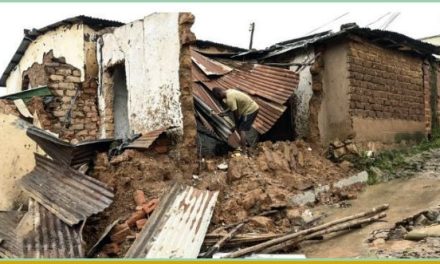

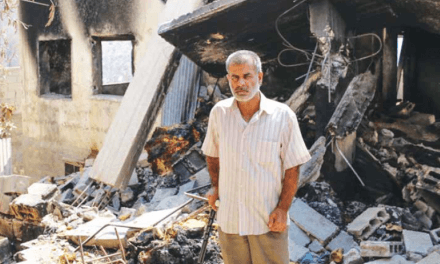

The Israeli army responded in its usual, heavy-handed way, and Israel’s defence minister, Moshe Ya’alon, called for a shoot first policy on ‘stabbers and stone throwers’. Neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem have been blockaded by Israeli occupation forces; extra police reservists and civil and border police have been deployed; and the homes of alleged attackers have been destroyed. This further worsened the situation, and the protests and attacks on soldiers have spread to other areas in the West Bank.

These incidents take place within a context of Israel’s increased and intensified control over East Jerusalem and the West Bank. Settler numbers have increased from 150 000 during the Oslo

negotiations in 1993 to over 500 000 in 2015, and, to protect these, Israel has instituted measures such as restrictions on Palestinian movement and a minimum ten year jail term for Palestinian’s convicted of stone throwing. Palestinians in the West Bank have also increasingly become victims of settlers’ ‘price tag’ attacks, with little or no repercussions for the perpetrators. The Israeli NGO Yesh Din reports that convictions are obtained in less than two per cent of cases and that over eighty-five per cent of cases are closed before the indictment stage.

Adding to Palestinian frustration, the Palestinian Authority has become increasingly ineffective. Corruption, a lack of political will,

and security coordination with Israel (a requirement of the Oslo Agreement), mean that many Palestinians view the PA as part of the problem. Many Palestinian youth

– born around the time of the Oslo negotiations or thereafter– have become disillusioned with the PA’s broken promises, causing them to seek different means of articulating their dissatisfaction. This has been compounded by a cynicism among Palestinians about the role of the international community and Arab states. With negotiations non- existent, Palestinians see no end in sight for the Israeli occupation as the region’s and the world’s attention is consumed by the growth of the Islamic State group (IS), and conflicts in Syria, Libya and Ukraine.

Most major Palestinian parties have responded in a haphazard and even contradictory manner. Fatah has called for calm, and deployed its security apparatus to quell the protests in some areas, leading many to accuse it of complicity. Later, it attempted to co-opt the protests, arguing that they were against the occupation. Hamas, on the other hand, expressed support for the protests, advocating the formation of a unified Palestinian position to defend and escalate the uprising. There is little chance, however, that Hamas will want to militarise the uprising from Gaza. It has been accused by some Palestinians of wanting to benefit from the crisis, and its hands-off approach – while repeatedly calling for unity – is likely so that it does not give the impression that it wants to take control of the uprising. It is noteworthy that no party has yet sought to take the lead and formally support the protests, especially the stabbings of Israeli soldiers and settlers. The uprising, thus, is largely a leaderless revolt of Palestinian youth.

Questions over whether this may herald the beginning of the Third Intifada abound, particularly since the people’s anger is similar to that which preceded the first two intifadas, and the lives of Palestinians are more miserable now, especially considering the dire socio-economic conditions of ordinary Palestinians. Compounding this is the hopelessness caused by the lack of leadership. However, the absence of a coherent national movement and established party support raises questions about the sustainability of the protests. It is debatable whether Palestinians will be able to continue the current protest actions and endure its consequences long enough to realise substantial change without the support of established political parties. Furthermore, political fragmentation and the impact of neoliberalism have prevented ordinary Palestinians from being able to formulate a unifying vision.

The Israeli government, supported by Jordan and the Middle East quartet (the USA, EU, Russia and UN), has announced that the status quo at Al-Aqsa will remain in force, and that surveillance cameras will be installed at the compound in an attempt to prevent the protests from spreading. However, this is a disingenuous attempt to deflect attention from the fact that Israel has already been working to alter facts on the ground.

In 2014, over 11 000 Jewish religious nationalist visitors were allowed into the compound, twenty-eight per cent up from the previous year and almost double the 2009 figure. Further, the frequency of these visits increased from bi-weekly in 2012 to around twice or thrice a week in 2014. In August, the head of the notorious Third Temple Movement, Yehuda Glick, privately met with Netanyahu, and subsequently claimed the government was attuned to the needs of fundamentalist Jews regarding Al-Aqsa. The struggle over protection of the compound is thus likely to further intensify and these provocations will ensure that protests endure. This is especially since the protests over Al-Aqsa are a reflection of dissatisfaction with the larger problem of Israel’s occupation, the corruption of the PA, and the lack of political leadership.